Celebrating Black pioneers in cancer research

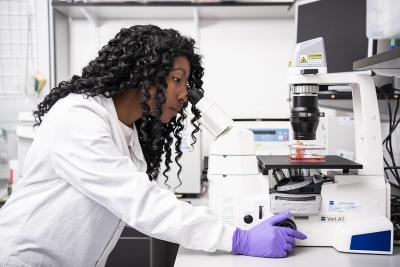

This Black History Month, we’re celebrating the contribution that Black scientists have made - and continue to make - to the advancement of cancer research and care.

- Published:

- Category:

- Race and identity

While their contributions may not always have been as widely acknowledged or celebrated as those of their white counterparts, Black scientists have played a vital role in the advancement of cancer treatment and care - a role that continues today with a new generation of Black cancer specialists who are at the cutting edge of their fields.

Jane Cooke Wright (1919–2013) was a pioneering cancer researcher and surgeon who developed new methods to evaluate cancer treatments using tumour biopsies. This led to new ways to administer chemotherapy and resulted in her appointment to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. She was also a founder of the American Society for Clinical Oncology, set up to support clinical research into cancer treatments. In 1971 she became the first female president of the New York Cancer Society.

Sigourney Bell is a PhD student at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute at the University of Cambridge. Her PhD focuses on developing treatments for a rare paediatric brain tumour, with the goal of creating new therapies for children with very limited treatment options. She is a co-founder of #BlackInCancer, which aims to empower and encourage future Black Cancer leaders and reduce cancer disparities through education and advocacy.

I’d worked for three pharmaceutical companies and never met a Black woman with a PhD. We wanted to create a space where there were role models.

Jewel Plummer Cobb (1924-2017) was an American biologist and cancer researcher. Most of her work focused on melanin, skin damage and the impact of chemotherapy drugs on cell division.

Cobb was initially denied a fellowship to study biology at university, allegedly due to her race, but was admitted after an interview. The granddaughter of a freed slave, she was the first woman of colour appointed to the National Science Board.

She was a passionate advocate for increasing representation of women and minority students. One former student, Timothy Yarboro, said that without her example, “I would not have become a doctor. Because of her, I knew it was possible.”

Henrietta Lacks (1920–1951) was not a clinician or a scientist, but her contribution to immunology and cancer research is no less important. Diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951, her biopsy would end up changing the course of cancer research. Henrietta’s tumour cells had remarkable survival capabilities and would double in number almost every day. With them, scientists could study the impact of drugs, viruses, radiation, and other treatments on cancer cells without needing to test them directly on patients. Unfortunately, as was common practice at the time, Henrietta’s cells were used for research without asking for her consent. Nevertheless, her legacy has undoubtedly changed the field of medicine and her cells continue to enable important discoveries in cancer, infectious diseases, and immunology.

Eric Aboagye is a Professor at Imperial College London, where he researches the use of innovative imaging techniques for cancer diagnosis. He’s also Director of the Comprehensive Cancer Imaging Centre, which combines synthetic chemistry, software development and biomedical science to diagnose and treat cancer patients. His cutting edge research recently demonstrated that artificial intelligence is significantly more accurate than blood tests in predicting the survival rates of ovarian cancer.